In the beginning – debt came first

In the beginning – debt came first

There we were, thousands of years ago, roaming around hunting and gathering, travelling in groups. At some point we started staying longer in certain places, maybe because there was good hunting, or a nice river with plenty of fish. Then we stopped travelling and planted food and built houses. In his History of Debt, anthropologist David Graeber talks about communism (you could call it ‘communitarianism’, the way we lived in community), being about ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’, in its simplest sense. He means that, for example, if someone said to you ‘Hold this wooden post, please, while I knock it in to the ground’, you didn’t say ‘What’s in it for me?’ you just did it, because it’s the most efficient way to put up a barn, using the contributions of everyone available, to best advantage.

Back then, what we couldn’t catch, grow or make, we would have to beg or borrow from our neighbour. They would give it to us because we’re friends, family. Because it’s very useful to have people in your debt. If they owe you then when you need something, you know where to go and cash in that favour. Then, when the favour is repaid, you’re even. You’re equals again.

What if you can’t repay a debt? What if you kill someone by accident? The English word ‘pay’ comes from ‘pacify’. It has been suggested that money, pieces of silver or whatever tokens we used, may have been invented to pay debts, as compensation for losses. So, debt was the first form of currency, payment came later. When you kept accounts (a ‘count’), they were tallies of what you owed, favours to be repaid. Or, what was owed to you, discs of leather, tally sticks and sometimes shells, indicating how many sacks of corn you had deposited in the communal barn, like cloakroom tickets to get your stuff back.

In country areas of the UK, people still go visiting on Christmas Eve and ‘settle up’. Whatever you have borrowed over the year, a barn load of hay, a chicken, or a book, you take it back to your neighbour so everything is straight for the next year. This is the idea of ‘reciprocity’ or ‘one good turn deserves another’.

This works on a small scale and a local level. It also works well when everyone has access to the same ‘stuff’, or resources, like ‘common’ land used to feed animals and grow food, fish in the rivers and water belonging to everyone.

Stuff, or resources, we can also call ‘capital’. ‘Natural capital’ (animal, vegetable and mineral) and ‘human capital’ (our labour) was traded for thousands of years before money.

Stuff, or resources, we can also call ‘capital’. ‘Natural capital’ (animal, vegetable and mineral) and ‘human capital’ (our labour) was traded for thousands of years before money.

Artefacts from 2,000 BC and the first civilizations of the ancient middle east record details of credit and ‘interest rates’ and how people came into the towns once or twice a year to pay their bill. Debt could also be cancelled. Every now and then it was good to wipe the slate clean. In Judaism, every seven years was a ‘Jubilee’ year, this meant debt cancellation, for everyone to start again.

The great credit-based ‘trading nations’ grew in Europe until about 600BC. The two greatest trading nations – the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians – were the last to mint coins.

So, debt came before money, and communism – in its oldest sense – before capitalism.

The Classical Age 600BC – 600AD

The Classical Age 600BC – 600AD

Then came the rise of three powerful civilizations, Greece, India and China, and the first records of ‘coins’. These great powers were growing and expanding and gradually colonising other people’s land. It was a time of enormous violence, pillage, rape and bloodshed. Armies had to be fed. You either had to use half your army to transport live animals and sacks of grain, or find a way to make the local people feed them. You could steal all their food but small towns and villages wouldn’t be able to feed thousands at a time.

So, you raised an army, ransacked the palaces and temples for their gold and silver and distributed it to your army in small measurable pieces, little bits of silver, minted and stamped with a picture of your face so they would clearly know who was in charge. Then, you made people pay taxes, not in food or cows, but in coins, and now you have embedded money into the population. You control the means of exchange. Coins were invented on the fringes of military operations whilst the peaceful trading cities continued to trade on credit, until they too were sacked and destroyed. It could be said that money came about because of war. War is expensive, especially if you keep killing the people who grow your food. Credit was replaced by the very worst kind of debt, the unsustainable kind, where people die of starvation.

In the Mediterranean, India and China, many people were reduced to ‘chattel slaves’ – owned as the property of another – and debt crises followed. The constitutions of ancient Athens and Rome were attempts to deal with debt crises. Where previously debt could be written off, in these coin-based societies, you had to throw money at the problem. If you wanted your citizens (non-females, non-slaves) to be available to fight in your wars you kept them happy by giving them coins in exchange for ‘civic duties’, liking sitting on councils or going to the theatre. This was an early way of moving wealth from rich to poor, you could call these payments ancient ‘benefits’.

In the Mediterranean, India and China, many people were reduced to ‘chattel slaves’ – owned as the property of another – and debt crises followed. The constitutions of ancient Athens and Rome were attempts to deal with debt crises. Where previously debt could be written off, in these coin-based societies, you had to throw money at the problem. If you wanted your citizens (non-females, non-slaves) to be available to fight in your wars you kept them happy by giving them coins in exchange for ‘civic duties’, liking sitting on councils or going to the theatre. This was an early way of moving wealth from rich to poor, you could call these payments ancient ‘benefits’.

This was a time of great cruelty, often called the Golden Age because of the rise of three movements: Philosophy, Religion and Poetry. These movements were essentially peace initiatives, opposing the cruelties of the times. Before they crashed, the great civilizations of Rome, China and India all tried to embrace their different religions, but it was too late, it was hard to recruit soldiers when crises caused by debt meant that you couldn’t pay them. The empires collapsed.

The Golden Age was over, but in those 1,200 years of brutality, money had become a physical thing you could hold in your hand.

Middle Ages 600AD – 1400s

Middle Ages 600AD – 1400s

Money became virtual again. Religion took control for a while (about 500 years). Motivated by the desire not to return to the debt crises of the Classical Era, power moved from soldiers to religious clerks. Because ‘interest rates’ cause debt to spiral out of control, all the major religions banned the charging of interest on credit agreements, or ‘usury’.

Christianity and Islam in the west, Buddhism and Confucianism in the east, became the dominant forces in society, operating an endless variety of credit arrangements (get your cow now, buy later), leather tokens, tally sticks.The Indian subcontinent by this time has ‘cheques’ (promises to pay later). Buddhist monasteries even ran pawn shops.

‘Trade’ was morally acceptable, and so was ‘profit’ (Mohammed was a merchant), but the ‘market’ was an extension of the principle of mutual aid. Reputation and reciprocal respect was the key to success. Cut-throat ‘competition’, as we have seen grow in recent history, would have been seen as a crime against God and controlled by religious law. In all the major religions, it still is.

The Conquistadores 1400s

The Conquistadores 1400s

In the 15th century there was a return to the power of war and slavery and it started in China. The paper money systems of the Mogols and the Ming Dynasty ended up in chronic inflation. Inflation happens when the ‘value’ of money goes down quickly, or becomes ‘devalued’ which means that prices rise rapidly. When the link between the actual value of ‘stuff’ and the money in circulation is lost, people lose faith in the currency itself. The reasons for inflation are complicated but, put simply, if you print too much money it stops being meaningful. It is worth less each day. For example, if one day a loaf of bread costs one ‘note’ and the next day it costs two, that’s chronic inflation and no one can live like that because wages don’t rise at the same rate. In 15th century China, people turned in desperation to uncoined silver, which seemed like it had ‘real’ value. But there was not much silver in Chinese mines, so they imported some from Japan and, when that source also dried up, from Mexico and Peru.

The colonisation by Europe of the mainland Americas would never have happened without the Chinese demand for silver. The conquest of Peru and Mexico by the Spaniard Hernan Cortes and the Conquistadores, was extreme in cruelty. The extent of the human suffering, the systematic destruction of human societies, the drive to extract gold and silver, the slavery, the rotting bodies piled up around the mines, was driven by debt, and couldn’t be further away from the idea of ‘reciprocity’ and ‘one good turn deserves another’.

The colonisation by Europe of the mainland Americas would never have happened without the Chinese demand for silver. The conquest of Peru and Mexico by the Spaniard Hernan Cortes and the Conquistadores, was extreme in cruelty. The extent of the human suffering, the systematic destruction of human societies, the drive to extract gold and silver, the slavery, the rotting bodies piled up around the mines, was driven by debt, and couldn’t be further away from the idea of ‘reciprocity’ and ‘one good turn deserves another’.

The idea of ‘colonial adventurism’ was to go into debt in order to raise funds to launch an expedition, to then have to service those debts ‘whatever it takes’. That is, no matter what you have to do, including bloodshed and torture. Was the conquistadores’ apparently insatiable appetite for plunder, a direct result of debt? Yes. Cortes had run up a huge personal debt before he launched his offensive. He promised his army untold riches to join him, which never materialised when the whole terrible episode ended in disaster. The justification for going into debt was: the success of previous expeditions and the promise of future ones. Thus, the Spanish ‘expanded’ into the Caribbean and then the mainland Americas. The logic being that, if an empire doesn’t expand, or ‘grow’, then it will somehow collapse upon itself. ‘New’ wealth must be created to pay old debt. Hence the idea of ‘growth’ that has led us to capitalism.

Slavery, war, debt and the Bank of England 15th century onwards

Slavery, war, debt and the Bank of England 15th century onwards

At school in the UK we learn about the ‘slave triangle’. It went like this:

-

- Ship owners in the English cities of Bristol and Liverpool acquired ‘stuff’ from local wholesalers, for example brass and copper, on credit. They then shipped it to African ports.

- They exchanged goods for people, ripping Africans from their families and communities in violent raids and later through debt contracts, then shipped these slaves to:

- North American plantations, where human life was exchanged for cotton and sugar to return to England to pay off the original debt, with the potential for massive profit, or potentially fantastic loss, too, if your ship sank, or all your slaves died of dysentery and misery on that stage of the journey.

The first two expeditions of the English East India Company in 1601 and 1604 returned to England with cargos of pepper, cloves and nutmegs, providing a profit to the shareholders of 95%. The ships in the third journey, in 1607, were wrecked on the way back and the investors lost all their capital. After twelve voyages, each financed separately, the company transformed itself into a joint-stock company, trading stocks on the London Stock Exchange. People could now invest in the company, in profits and losses made over years, rather than one voyage, as a way of spreading the risk of long-distance trade over different ventures.

The first two expeditions of the English East India Company in 1601 and 1604 returned to England with cargos of pepper, cloves and nutmegs, providing a profit to the shareholders of 95%. The ships in the third journey, in 1607, were wrecked on the way back and the investors lost all their capital. After twelve voyages, each financed separately, the company transformed itself into a joint-stock company, trading stocks on the London Stock Exchange. People could now invest in the company, in profits and losses made over years, rather than one voyage, as a way of spreading the risk of long-distance trade over different ventures.

Capitalism was born. It worked like this: you put your money in, you sit back and wait for it to multiply, without doing any work yourself. Money makes money. It’s worth noting that profits like 95% are only possible because of distance. Nutmeg is rare because it’s foreign. No-one is going to give you inflated prices for wheat, for example, which grows in the field next door. If it’s a bit messy, all the bloodshed and misery of slavery, no-one at home sees it if it’s happening on the other side of the world. Racist ideas, that said that white people were superior to black people, that black people somehow had less rights to respect and humanity – even that they had no ‘souls’ because they weren’t Christian – were a way of dealing with any guilt about how Europe treated the rest of the world.

So, the selling of human souls through colonialism and military ventures – driven by debt – led to stock markets, bond markets, limited liability corporations and in 1694 to the establishment of the Bank of England, which was essentially a war fund.

So, the selling of human souls through colonialism and military ventures – driven by debt – led to stock markets, bond markets, limited liability corporations and in 1694 to the establishment of the Bank of England, which was essentially a war fund.

King William of England needed to pay off his debts from the ‘30 Years War’ in Europe (1618-1648). He got together a group of private bankers and offered them a monopoly on the management of the national debt. Capitalists were basically holders of government bonds. These bonds paid interest, as a reward for investment. It was a sweet deal. The money men needed political protection and the politicians needed money.

Since then, all money has been about circulating the king’s debt. We don’t move money around, we move debt. The clue is on the bank notes, ‘I promise to pay the bearer…..’ The note is a promise, a promise to provide the equivalence in value of actual stuff. It’s not real in and of itself. If money was real, the Cayman Islands (where the rich stash their money to avoid paying tax on it) would have sunk by now.

The original debt to King William can never be repaid. If the Queen tried to cash it in, the entire British banking system would essentially disappear. All modern nation states run on deficit finance and maintain a national debt.

The growth of capitalist production

The growth of capitalist production

Whilst merchant capitalists invested their money in government wars, most people were making and selling ‘stuff’. Starting at home or in small workshops, the manufacture of cooking pots, woollen clothe, knives, tools, soap, ribbons, braid, buttons , pins, nails, bricks, tiles and other useful objects grew, until in 16th century England over half of all households were dependent on income from wage labour instead of local reciprocal credit arrangements. People now had money to buy goods. Markets grew in towns and in Britain particularly in London, with goods flowing in and out of the city.

‘Journeyman (meaning ‘day-worker’) Societies’, or ‘Friendly Societies’ were the first labour movements. Craftsmen organised themselves into support groups to try to push up their wages, whilst employers strove to keep them down, to maximise their profits. ‘Strikes’ – the withholding of labour to improve working conditions – are recorded as early as the 15th century in Britain.

This recent period of about 500 years in the west has seen the end of the local credit arrangements between baker and shoemaker, based on social obligation and mutual need and cooperation, replaced by the minting of millions of little coins and the rise of the myth that money is a thing. The old credit agreements that defined communal life, you could even say were the substance of human society – debt – became a crime. Being sent to ‘debtors’ prison’ in 1870, if you were poor, was often a death sentence.

The loss of common capital

The loss of common capital

The second half of the last millennium in Britain and Europe saw the movement of people from the countryside to the cities. We have seen how in early ‘communal’ societies – and today still in large parts of the world – ‘reciprocity’ is possible when everyone has access to similar resources, particularly to common land.

The ‘enclosure’ movement between the 15th and the 19th centuries in Britain fenced off common land – and small strips of land that had been used for generations by the poor to feed themselves – and divided them into larger blocks owned by single ‘landowners’.

Feudal lords had lived off their ‘rights’ to receive labour and goods from unfree peasants but, as these relationships gave way to the ‘markets’, lords looked for other ways of getting ‘paid’, living off ‘rent’ from tenant farmers who had to compete for these tenancies and pay for ‘wage labour’.

Feudal lords had lived off their ‘rights’ to receive labour and goods from unfree peasants but, as these relationships gave way to the ‘markets’, lords looked for other ways of getting ‘paid’, living off ‘rent’ from tenant farmers who had to compete for these tenancies and pay for ‘wage labour’.

Land that had been a common resource for all, natural capital that had allowed people to feed themselves, albeit in abject poverty, had now become ‘property’, a commodity that could be bought and sold. It was essentially a theft of land from poor people, by the rich.

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution

Earlier small industrial enterprises, funded by families or local loans, were gradually replaced by larger and larger corporations, made possible by the innovation of stock markets and increasingly sophisticated banking systems that could spread risk, and advances in book-keeping that oiled the mechanisms of European trade.

The flow of skilled labour around Europe was increased by the movement of refugees. People from Italy to Switzerland, Germany, Holland and England. Huguenots, French Protestants and Calvinists to England and Switzerland and Jews from Iberia to all over Europe. These women and men brought with them their skills in watch-making, silk-weaving and lace-making.

Merchant capital began to get heavily involved in mining in northern and central Europe, of copper, gold, silver and lead, which became more and more expensive the deeper we dug and needed substantial investment.

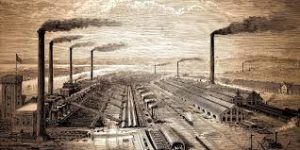

Technological advances were made possible by the financial ‘markets’ as they developed. This led to what we now call the ‘Industrial Revolution’. In the 1800s, textile mills and then steam engines and railways, were dependent on coal and the coal-mining industry, all financed through the banks and the stock exchange.

The rise of industrial towns and cities in Northern Europe, characterised by smoking chimney stacks and slum housing, saw the decisive move of European populations from country to city, from feudal society to wage slavery.

Economics

Economics

So, gone are the social credit contracts, replaced by money as a concept, as an idea of a tangible thing that actually exists, in and of itself.

So sure are we that it exists, that we tried to turn it into an actual science.

Economists have attempted to find the formula for a ‘stable economy’ and economic ‘growth’.

By growth, they mean that each generation gets a bit richer than the last. By stable, they mean that ‘inflation’ doesn’t get so high that money becomes ‘devalued’, and drops in value so fast that you have to take a wheelbarrow of paper money to buy one loaf of bread, as happened in Germany in 1923 at the beginning of the ‘Great Depression’.

The Gold Standard

The Gold Standard

The idea is that one unit of currency is worth an equivalence in stuff. So if you pay $1 for one loaf of bread, this represents the ‘cost’ of a loaf of bread. In an attempt to keep that ‘price’ stable, banking tied the value of currency to gold. The Bank of England had ‘gold reserves’, actual tons of bullion. When they lent out £1 to smaller banks, the theory was that it was a loan against an equivalent amount of gold in the bank. So there would always only be so much money in the world because the amount of gold was limited and you couldn’t put more money in circulation than there was actual gold. This, it was believed, prevented inflation.

This also was not entirely true. We have already seen that the Bank of England was founded on debt. And if all those debts had been called in, all at once, there wouldn’t have been enough gold in the banks. But it created the illusion of a solid weight of stability, confidence and good common sense. It dissuaded people from spending and borrowing too ‘unwisely’. It also perpetuated the myth that money was an actual thing, which had a value in and of itself.

Banks needed to encourage people to save (banks borrowing customers’ money), or they wouldn’t have the money to lend. The interest paid to savers was lower than the interest charged to borrowers, that’s how the banks made money. Interest rates could be manipulated to encourage people to save and to borrow. But the total amount of money available was governed by how quickly gold could be dug out of the ground.

Don’t mistake economics for a science

Don’t mistake economics for a science

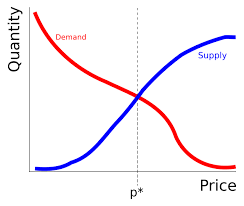

Part of trying to make money scientific was trying to invent mathematical formulas, ‘models’ to not just explain the flow of money, but to control it. A simple one is: price minus cost equals profit (sale price, minus cost of production/transportation/marketing/wages etc., equals how much you’re left with). Economists invented models to balance ‘supply and demand’ (if you produce more than people want to buy, the price does down, and vice versa).

In the early 20th century ‘quantity theory’ said that MV = PT (The quantity of money (M) times the velocity (V) at which it is spent, equals average price (P) times total number of transactions (T). )

Don’t worry about trying to understand that. It doesn’t mean much anyway. The reason economists keep coming up with new theories and models is that they haven’t found one that works yet.

But the main thing is to avoid people starving, now that – in the western world – the poor had no land to grow food. For this reason employment, and unemployment, has been a central theme of 20th century economics. In looking for economic ‘equilibrium’, a great deal of attention was given to the relationship between the ‘cost of living’ and unemployment rates, between wages paid in money and prices charged in money.

Next: Why It Broke